“That’s why this is the plastic area, you know? The Lebanese dream,” Zac Allaf of the Syrian hip-hop duo Bilad El-Sham says of the areas of Hamra, Downtown Beirut, and Gemmayzeh. “It’s like Los Angeles.” As an artist, you have to live in these areas even though the cost of living is high because they are where the audience is, he adds.

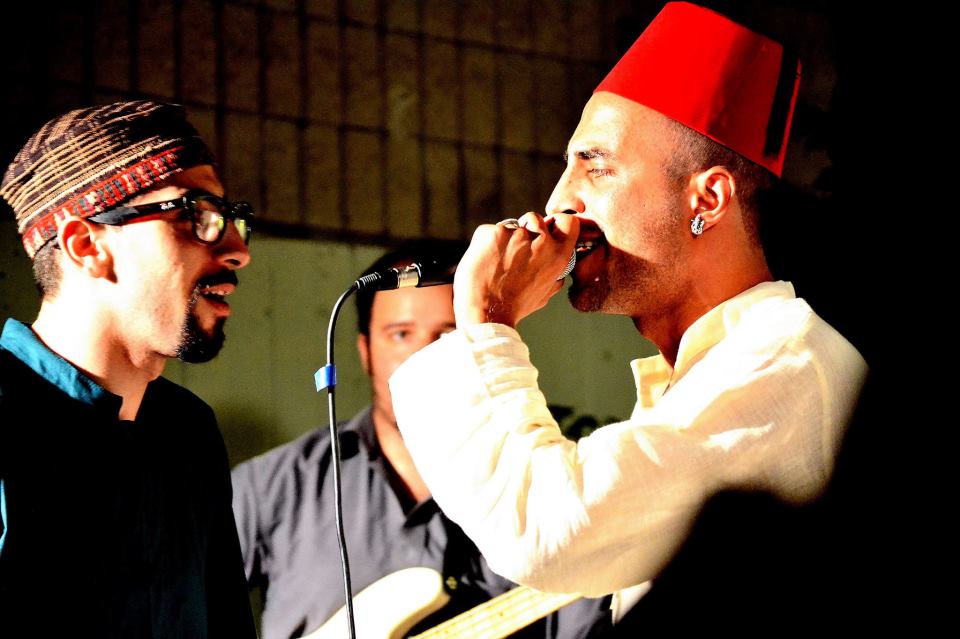

Allaf, who performs as Assasi Nun Fuse, came to Beirut six months ago with his friend and partner-in-music Wahid Al-Jabri, who performs as Cheb Wahid. Allaf and Al-Jabri are both from Aleppo, but met in Damascus and began making music together in 2006. They came to Beirut to audition for the television show “Arabs Got Talent.”

Bilad El-Sham’s music combines hip-hop with a style of traditional Algerian singing called Rai. Allaf began composing hip-hop songs in 2002. A neighbor in Aleppo helped him to arrange his lyrics with musical rhythms. “I can take images from everything that happens around me and write it in the lyrics,” he says.

Al-Jabri started learning to sing Algerian Rai music from a friend in Aleppo in 2000. He had the idea of combining Rai with hip-hop before meeting Allaf. No one was working with both traditional Arabic music and hip-hop before. Bilad El-Sham is among the first to experiment with incorporating these different influences into their music, Al-Jabri says.

Before forming Bilad El-Sham, Al-Jabri collaborated as a featured artist on a previous project that Allaf produced with another group in 2008. However, complications with the recording studio in Syria they were working with prevented the album from being released. The duo then took three years to work on the music for their new album, which they finished last year and recorded in one day.

Bilad El-Sham’s new album titled “Clinic of Bilad El-Sham” addresses the situation in the Middle East during the past two years. “We had bad times around Arabia the last two years with the political situation,” Allaf says. “We lived in a bad society in this time, and we are talking about the daily life.”

However, Bilad El-Sham’s music is not political. “We are talking about how we live,” Allaf emphasizes. “No politics.” Instead, their songs talk about topics such as immigration, the media and the shallowness of Arabic pop music.

One song addresses the issue of kids using drugs. “Many of the general youth have good talents and good thinking. They lose it when they do drugs,” Allaf says. So Al-Jabri and Allaf composed a song that addressed the topic using humor to tell youth not to do drugs.

Another song was inspired by a conversation they had with a man with Down's Syndrome on a street in Damascus. People passing him on the street assumed he couldn’t speak or think, but when Allaf and Al-Jabri talked with him they found out he spoke three languages. After the conversation they were like friends, Allaf says. “We don’t need to be like them to feel them,” he adds.

The album is called “Clinic of Bilad El Sham” because it is addressing issues people deal with in their daily lives that are not always talked about openly. “We have the same problems and we can’t say it in public,” Allaf says of different groups living in Syria and Lebanon. “We have the same pain, the same difficulties about immigration, and drugs, and music, and the media.” The album talks about these issues and makes them public. “A lot of people talk about politics, and they are good at it. So we don’t have to be like them. We have to do something new,” Allaf adds.

“There isn’t much respect for new ideas in Syria,” however, Allaf says about music and art. “So it is hard for all artists from Syria even if they play rock, or guitar, or rap, or anything… They have problems if they have new ideas for the scene.” The existent Syrian art scene has given them good ideas, he adds, but “we have to cross the lines.”

The media environment in Beirut is not much better. If you are not saying the word “habibi” in every song the mainstream media is not interested, Al-Jabri continues.

“We are against the mainstream,” Allaf adds. “It’s not up to media and fame. We don’t need fame.” Maybe we do need fame, he continues, to be able to survive as artists.

In Beirut people have open minds, Allaf says, “especially the Syrian people in Beirut.” Bilad El Sham’s biggest audience right now is Syrians living in Beirut, but the size of the audience, both Syrian and Lebanese, and their interest in new music are inconsistent.

The cost of living in Beirut also makes life difficult, Allaf says. “It’s hard for everyone, especially musicians. We have to work, and to work on our music.” Allaf and Al-Jabri both work in restaurants during the day and work on their music at night. Artists in Lebanon are like a family, Allaf continues. Instead of a sense of competition, artists support each other.

Beirut’s famous linguistic cosmopolitanism is also a source of frustration for Allaf and Al-Jabri. Lebanese will come up to them and start speaking in English. “I hate this,” Allaf says. He is not against people speaking languages other than Arabic, but “we are Arabs, and my mother tongue is Arabic,” he says.

The Arabic language is important to the culture, Al-Jabri adds. If people don’t speak to each other in Arabic or make art in Arabic a part of the culture is lost.

“We have to preserve our culture in a right way. That’s why we are called Bilad El-Sham,” Allaf concludes.

Beirut is like the weather, Allaf says. “You can’t know if today is raining or sunshine. Everyday is different in Beirut, but it’s still a cultural center for music.”

“Clinic of Bilad El-Sham” is scheduled to be released in February and will hopefully be available at the Virgin Megastore in Downtown Beirut and throughout the Arab world. Information about Bilad El-Sham’s upcoming events and music can be found on their Facebook page, Reverb Nation, and Twitter.

Eric Reidy is a project assistant at the SKeyes Center for Media and Cultural Freedom researching and writing about the cultural scene in Beirut. This article is part of a regular interview series with artists living, working, and creating in Beirut.

Previous articles:

- “Beirut Has a Special Magic”: An interview with Syrian artist Gylan Safadi

- “Our Culture is Dying”: An interview with Mohamad Hodeib