On November 5, 2024, Lebanese media personality Hicham Haddad posed a critical question in a viral social media video: “Are we winning the war? Or have we won the war?”

The video, which garnered half a million views on Instagram, emerged amid escalating pro-axis[1] victory rhetoric on social media and in the context of Israel's invasion of Lebanon, 22 days before the ceasefire was announced. The conflict had led to relentless bombings across the country, targeting Beirut’s southern suburbs, areas inside the capital, the South, the Bekaa, Mount Lebanon, and the North. Haddad’s remarks ignited sharp divisions in public opinion:

Compounding the controversy, Israeli social media pages picked up the video, leveraging it as part of Israel’s documented online strategy – a subject explored in a previous report.

Figure 1: Israeli accounts re-post Hicham Haddad’s video

The backlash against Haddad escalated into a campaign of incitement and even death threats. Haddad publicly expressed fear for his safety, stating that he felt threatened and hesitant to return to Lebanon – a concern rooted in alarming precedents: the assassination of writer and activist Lokman Slim, the assaults on journalists Nabil Mamlouk, Daoud Rammal, and Rami Naim, as well as the smear campaign targeting Mariam Majdouline Lahham.

This report analyzes the public discourse surrounding Haddad’s video, identifies dangerous statements, and investigates their origins and intentions.

The analysis focuses on conversations on X (formerly Twitter). Using data scraping techniques, all tweets containing the keyword "هشام حداد" were collected from November 5 to November 15, 2024.

The data was categorized thematically, and each tweet was tagged by sentiment:

A deep profile analysis of the sources behind inciting and dangerous tweets was conducted to identify patterns and triggers fueling the discourse.

After filtering out hashtag aggregators (irrelevant tweets using the hashtag to gain visibility), the final dataset comprised 865 tweets:

Sentiment Breakdown by Theme:

Cross-Platform Migration

Figure 2: Pro-Hezbollah account makes the video viral

User-Generated Content

Figure 3: Pro-Hezbollah journalist Pierre Abi-Saab, among others, responds to Haddad

Comparative Analysis: Organic or Orchestrated?

We examined three cases: Hisham Haddad, Ghassan Saoud, and Saleh Mashnouk.

To explore whether the backlash on Hicham Haddad was organic or orchestrated, we analyzed two other cases of prominent political commentators: Ghassan Saoud and Saleh Machnouk.

For background, Hicham Haddad, once a supporter of the Free Patriotic Movement (FPM), shifted to anti-Hezbollah position during the 2019 uprising. This shift made him a frequent target of FPM-aligned electronic avatar armies. Haddad’s broad appeal across diverse political audiences likely contributed to the significant response his video received.

Observations and Triggers

The virality of Haddad’s video can be attributed to two factors:

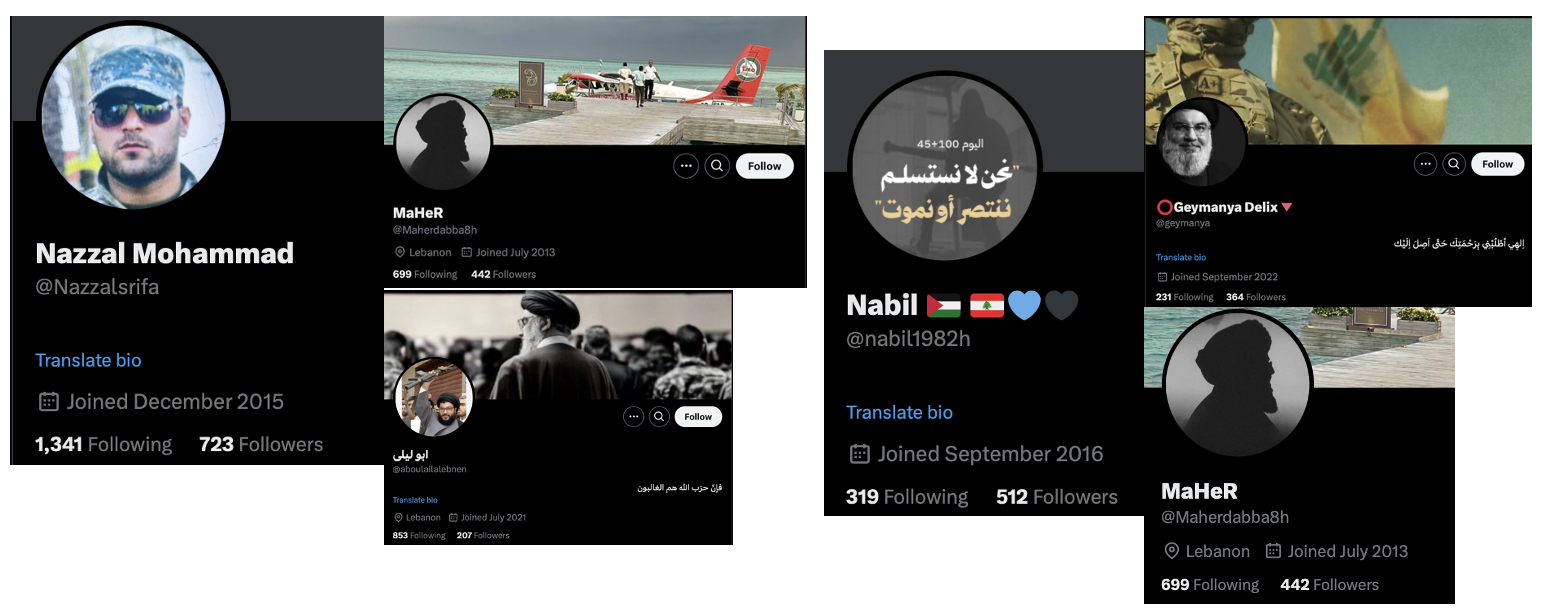

Figure 4: Example of avatars involved in attacking Haddad

Activity Levels and Longevity

The accounts involved in the discourse display varying levels of activity and longevity, indicating a mix of long-standing and newly created profiles: Old accounts (established in 2011, 2012) suggest sustained engagement from established users; and newer accounts (created in 2023, 2024) point to possible recent mobilization efforts, either organic or orchestrated.

Figure 5: Top 3 accounts with larger number of posts

Deleted or Suspended Accounts

Some accounts were suspended or deleted, likely due to platform enforcement of policies against violations such as hate speech.

The deletion of accounts – an occurrence noted in previous studies – suggests an awareness among users of their digital footprint. This behavior indicates a deliberate strategy to evade detection, with users frequently creating new accounts to sustain or launch new campaigns.

Figure 6: Example of suspended or deleted accounts

Geographical Indicators

More than half of the accounts had not entered their geolocation as it remains voluntary and it’s often used to deliver a message rather than indicate the real location. “Planet earth’ or “Ya Zahraa Madad-يا زهراء مدد” or even “Next to Nasrallah” were some of the location inserted. Several accounts claimed connections with countries such as Syria (6 accounts), Yemen (6 accounts, , Iraq (6 accounts), Jordan (2 accounts), Iran (1 account), and Palestine (4 accounts), Algeria (2 accounts), Morocco (2 accounts), UAE (4 accounts), Qatar (2 accounts), UK (4 accounts), France (4 accounts), and other countries, indicating cross country virality.

Figure 7: Foreign accounts join the campaign

Electronic Army or Human Accounts?

The Majority of the accounts showed no sign of autonomous behavior indicating real human tweets as opposed to a conventual bot army.

Incitement and Accusation of Treachery

This theme is characterized by highly charged rhetoric targeting Hicham Haddad and others, framing him as a traitor and a Zionist. The accusations range from direct insults to threats of future punishment.

Key observations:

Redefining Winning

This theme seeks to construct an alternative framework for interpreting victory and defeat, directly challenging Hisham Haddad’s narrative. Historical, ideological, and religious arguments are employed to redefine what constitutes victory. Key observations:

The recent online campaign targeting Hicham Haddad reflects a broader, recurring trend in Lebanon, where public figures critical of Hezbollah often become subjects of systematic incitement and smear campaigns on social media, especially on X. Despite X’s limited reach in Lebanon – only about 9% of the population uses the platform – it remains a key space for professionals, journalists, NGOs, and coordinated groups, including Hezbollah-aligned avatar accounts.

The analysis suggests that most of these accounts do not appear automated but operated by individuals skilled in content creation and monitoring. These actors take initiative and align with the trending hashtags or narratives, amplifying Hezbollah’s ideological strategy and setting the daily agenda for supporters all over the world.

In Hicham Haddad’s case, the effort was significant. Within three to four days, 18 original pieces of media content – including response videos, animations, and even a song with a full video clip accusing him of Zionist allegiance – were produced. This level of production indicates both time and resources were invested. Notably, a video criticizing Haddad, initially shared by a Hezbollah-aligned account, garnered 300,000 views in just a few hours and eventually reached 600,000 views, suggesting its distribution was amplified through large public forums such as Telegram or WhatsApp. Another indicator of cross-platform dissemination is original video content shared by multiple accounts, suggesting they have received or downloaded the original file.

The behavior of these digital actors reflects Hezbollah’s communication strategy of empowering individuals, as articulated by Imad Mughniyah, one of the founding fathers of Hezbollah. His emphasis on the “power of the individual” within the organization appears to manifest online, where ideologically driven individuals -often operating from Lebanon, Iraq, Syria, and even Europe – act as autonomous “defenders” of Hezbollah’s narrative. They coordinate instinctively, much like a “pack of wolves responding to a single howl,” and often delete comments or accounts to evade detection. This decentralized yet unified behavior blurs the line between organized orchestration and organic response.

Additionally, some avatar accounts frequently use viral hashtag to either amplify a certain tweet with the aim to reach a wider audiences, or to deliver a subtle message that gets lost in the echo chamber like a needle in a haystack. This opens a question about the understanding of some avatar accounts that the hashtags are monitored by relevant parties. For example: after as Israeli strike on the town of Kahalé, in Mount Lebanon, an anonymous account tweeted: “Do not trust the Syrian army that gives you weapons; they are passing info to the Mossad.”

This information could have been trivial had it been tweeted from a standard account. However, since it came from an avatar account, using the Hicham Haddad hashtag – where it only garnered 150 views – suggests its intention was not to maximize public reach but to act as a message. Such accounts, often with usernames resembling coded structures like “alixswh3386267,” may be used to deliver sensitive information or advice in plain sight.

Additionally, dozens of accounts appeared to have been created shortly before the campaign began, further indicating premeditated participation. While these individuals may not know each other personally, they are likely connected through shared ideological forums and platforms. Whether Hezbollah directly instructs them to act or simply relies on its planted ideology, the result is a coordinated digital response that amplifies the group’s narratives across the Arab world and beyond.

[1] Hezbollah, Islamic Republic of Iran, Syrian regime, Hamas, Popular Mobilization Units in Iraq, and Houthis in Yemen.

This report is published with the support of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The contents of the report are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.